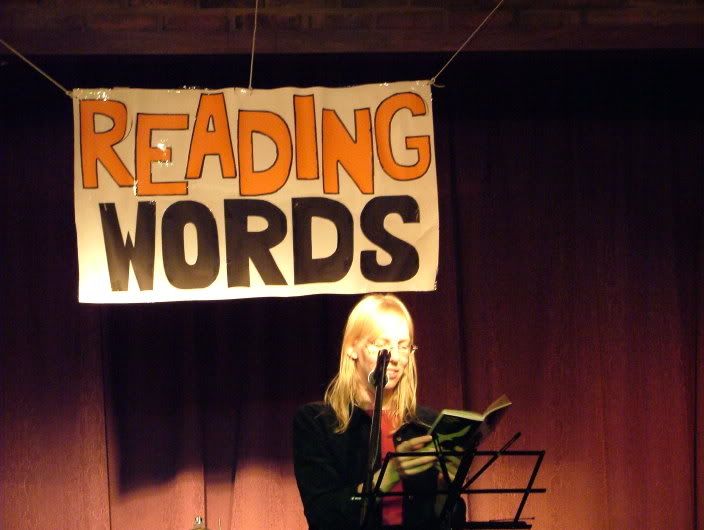

Amanda Hare (4-23-06)

Amanda read from the book Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach. Here are the excerpts that she read.

By sunup, Jonathan Gull was practicing again. From five thousand feet the fishing boats were specks in the flat blue water, Breakfast Flock was a faint cloud of dust motes, circling.

He was alive, trembling ever so slightly with delight, proud that his fear was under control. Then without ceremony he hugged in his forewings, extended his short, angled wingtips, and plunged directly toward the sea. By the time he passed four thousand feet he had reached terminal velocity, the wind was a solid beating wall of sound against which he could move no faster. He was flying staight down, at two hundred miles per hour. He swallowed knowing that if his wings unfolded at that speed he'd be blown into a million tiny shreds of seagull. But the speed was power, and the speed was joy, and the speed was pure beauty.

He began to pullout at a thousand feet, wingtips thudding and blurring in that gigantic wind, the boat and the crowd of gulls tilting and growing meter-fast, directly in his path.

He couldn't stop; he didn't know yet even how to turn at that speed.

Collision would be instand death.

And so he shut his eyes.

It happened that morning, then, just after sunrise, that Jonathan Livingston Seagull fired directly through the center of Breakfast Flock, ticking off two hundred twelve miles per hour, eyes closed, in a great roaring shriek of wind and feathers. The Gull of Fortune smiled upon him this once, and no one was killed.

By the time he had pulled his beak straight up into the sky he was still scorching along at a hundred and sixty miles per hour. When he had slowed to twenty and stretched his wings again at last, the boat was a crumb on the sea, four thousand feet below.

His thought was triumph. Terminal velocity! A seagull at two hundred fourteen miles per hour! It was a breakthrough, the greatest single moment in the history of the Flock, and in that moment a new age opened for Jonathan Gull. Flying out to his lonely practice area, folding his wings for a dive from eight thousand feet, he set himself at once to discover how to turn.

(p. 27-29)

...

The gulls were flocked into the Council Gathering when he landed, and apparently has been so flocked for some time. They were in fact, waiting.

"Jonathan Livingston Seagull," said the Elder, "Stand to Center for Shame in the sight of your fellow gulls!"

It felt like being hit with a board. His knees went weak, his feathers sagged, there was a roaring in his ears. Centered for shame? Impossible! The Breakthrough! They can't understand! They're wrong, they're wrong!

"...for his reckless irresponsibility," the solemn voice intoned, "violating the dignity and tradition of the Gull Family..."

A seagull never speaks back to the Council Flock, but it was Jonathan's voice raised. "Irresponsibility? My brothers!" he cried. "Who is more responsible than a gull who finds and follows a meaning, a higher purpose for life? For a thousand years we have scrabbled after fish heads, but now we have a reason to live-to learn, to discover, to be free! Give me one chance, let me show you what I've found..."

Jonathan Seagull spent the rest of his days alone, but he flew way out beyond the Far Cliffs. His one sorrow was not solitude, it was that other gulls refused to believe the glory of flight that awaited them; they refused to open their eyes and see.

He learned more each day. He learned that a streamlined high-speed dive could bring him to find the rare and tasty fish that schooled ten feet below the surface of the ocean: he no longer needed fishing boats and stale bread for survival. He learned to sleep in the air, setting a course at night across the offshore wind, covering a hundred miles from sunset to sunrise. With the same inner control, he flew through heavy sea-fogs and climbed above them into dazzling clear skies...in the very times when every other gull stood on the ground, knowing nothing but mist and rain. He learned to ride the high winds far inland, to dine there on delicate insects.

What he had once hoped for the Flock, he now gained for himself alone; he learned to fly, and was not sorry for the price that he had paid. Jonathon Seagull discovered that boredom and fear and anger are the reasons that a gull's life is so short, and with these gone from his thought, he lived a long fine life indeed.

(p. 38-41)

They came in the evening, then, and found Jonathan gliding peaceful and alone through his beloved sky. The two gulls that appeared at his wings were pure as starlight, and the glow from them was gentle and friendly in the high night air. But most lovely of all was the skill with which they flew, their wingtips moving a precise and constant inch from his own.

Without a word, Jonathan put them to his test, a test that no seagull had ever passed. He twisted his wings, slowed to a single mile per hour above stall. The two radiant birds slowed with him, smoothly, locked in position. They knew about slow flying.

He folded his wings, rolled and dropped in a dive to a hundred ninety miles per hour. They dropped with him, streaking down in flawless formation.

At last he turned that speed straight up into a long vertical slow-roll. They rolled with him, smiling.

He recovered to level flight and was quiet for a time before he spoke. "Very well," he said, "who are you?"

"We're from your flock, Jonathan. We are your brothers." The words were strong and calm. "We've come to take you higher, to take you home."

"Home I have none. Flock I have none. I am Outcast. And we fly now at the peak of the Great Mountain Wind. Beyond a few hundred feet, I can lift this old body no higher."

"But you can, Jonathan. For you have learned. One school is finished, and the time has come for another to begin."

As it had shined across him all his life, so understanding lighted that moment for Jonathan Seagull. They were right. He could fly higher, and it was time to go home.

He gave one last look across the sky, across that magnificent silver land where he had learned so much.

"I'm ready," he said at last.

And Jonathan Livingston Seagull rose with the two star-bright gulls to disappear into a perfect dark sky.

(p. 52-53)

In the days that followed, Jonathan saw that there was as much to learn about flight in the place as there had been in the life behind him. But with a difference. Here were gulls who thought as he thought. For each of them, the most important thing in living was to reach out and touch perfection in that which they most loved to do, and that was to fly. They were magnificent birds, all of them, and they spent hour after hour every day practicing flight, testing advanced aeronautics.

For a long time Jonathan forgot about the world that he had come from, that place where the Flock lived with its eyes tightly shut to the joy of flight, using its wings as a means to the end of finding and fighting for food. But now and then, just for a moment, he remembered.

He remembered it one morning when he was out with his instructor, while they rested on the beach after a session of folded-wing snap rolls.

"Where is everybody, Sullivan?" he asked silently, quite at home now with the easy telepathy that these gulls used instead of screes and gracks. "Why aren't there more of us here? Why, where I came from there were..."

"...thousands and thousands of gulls. I know." Sullivan shook his head. "The only answer I can see, Jonathan, is that you are pretty well a one-in-a-million bird. MOst of us came along ever so slowly. We went from one world into another that was almost exactly like it, forgetting right away where we had come from, not caring where we were headed, living for the moment. Do you have any idea how many lives we must have gone through before we even got the first idea that there is more to life than eating, or fighting, or power in the Flock? A thousand lives, Jon, ten thousand! And then another hundred lives until we began to learn that there is such a thing as perfection, and another hundred again to get the idea that our purpose for living is to find that perfection and show it forth. The same rule holds for us now, of course: we choose our next world through what we learn in tis one. Learn nothing, and the next world is the same as this one, all the same limitations and lead weights to overcome."

He stretched his wings and turned to face the wind. "But you, Jon," he said, "learned so much at one time that you didn't have to go through a thousand lives to reach this one."

In a moment they were airborne again, practicing. The formation point-rolls were difficult, for through the inverted half Jonathan had to think upside down, reversing the curve of his wing, and reversing it exactly in harmony with his instructor's.

"Let's try it again,"Sullivan said over and over: "Let's try it again." Then, finally, "Good." And they began practicing outside loops.

One evening the gulls that were not night-flying stood together on the sand, thinking. Jonathan took all his courage in hand and walked to the Elder Gull, who, it was said, was soon to be moving beyond this world.

"Chiang..." he said, a little nervously.

The old seagull looked at him kindly. "Yes, my son?" Instead of being enfeebled by age, the Elder has been empowered by it; he could outfly any gull in the Flock, and he had learned skills that the others were only gradually coming to know.

"Chiang, this world isn't heaven at all, is it?"

The Elder smiled in the moonlight. "You are learning again, Jonathan Seagull," he said.

"Well, what happens from here? Where are we going? Is there no such place as heaven?"

"No, Jonathan, there is no such place. Heaven is not a place, and it is not a time. Heaven is being perfect." He was silent for a moment. "You are a very fast flier, aren't you?"

"I...I enjoy speed," Jonathan said, taken aback but proud that the Elder had noticed.

"You will begin to touch heaven, Jonathan in the moment that you touch perfect speed. And that isn't flying a thousand miles an hour, or a million, or flying at the speed of light. Because any number is a limit, and perfection doesn't have limits. Perfect speed, my son, is being there."

Without warning, Chiang vanished and appeared at the water's edge fifty feet away, all in the flicker of an instant. Then he vanished again and stood, in the same millisecond, at Jonathan's shoulder. "It's kind of fun," he said.

(p. 60-65)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home